Victor Rodríguez and the revival of the Hyper-realism.

By Raquel Tibol

Among the new forms of the figurative that arose after Pop Art, hyper-realism has polarized opinions more than most with respect to its aesthetic validity. It is also been called radical realism, photo realism, ultra-realism and even precisionism.

Veritable and exact representation, the dependency on photography (pre-existing or taken ad hoc), the restoration of certain traditional values, the subjection of the eye to a deceptive fidelity, the always magnified real dimension, prompted many to describe hyper-realism as artifice and regard its postulates with some susupicion. Its detractors predicted its eclipse in less than a decade from its appearance. Indeed, its wanings, which occurred in various periods, were temporary. Hyper-realism, as a changing aesthetic system with its own stylistic pluralism has won the attention, over and over again, of a demanding segment of the public. A segment that has appreciated in it the concord of art and design, of invention and document and of a time that always inserts itself into the present.

Hyper-realism took off in the U.S. and gained prestige in Europe in only six years. It was heralded in the exhibition entitled The Photographic Image, presented in 1966 at the Guggenheim in New York. Within three years, there was sufficient production for two establishing exhibition: Paintings from photo at the Riverside Museum and Aspects of a New Realism at the Milwaukee Art Center. In 1970, hyper-realismearned places at the Whitney and at the Montreal Museum. In 1972, New York's prestigious Sidney Janis Gallery showeda carefully mounted selection entitled Sharp-focus realism, whereas at the documenta V, Kassel, Germany, it was situated as one of the most outstanding innovations of the moment, worldwide.

Suddenly, in 1996, when hyper-realism was no longer questioned, Victor Rodriguez pleasantly surprised the judges at the XVI National Meeting of Young Artists in Aguascalientes, (I was one of the five), his colleagues and viewers of all levels. His Gran cabeza/Big head (acrylic/canvas, 2m x 2m) of a woman with her tongue out and a fly on her cheek, had been executed with steel graver and brush a year before. Its attributes reveal not only a clear consciousness of style but also a daring determination to recycle it. The latter was an implicit promise that he has amply fulfilled, with effort and excellent results, demonstrated by his oeuvre from 1988 to 1999, and now presented at the Galería Enrique Guerrero.

The OED defines recycling as a "consistent operation subjecting a material again to a total or partial cycle of treatment, when the change in that material turns out to be incomplete". This definition may be applied to Victor Rodríguez' efforts. If hyper-realism's preponderant characteristic was its distancing, he would make it intimate. If the first hyper-realism had confronted conceptual art he would assimilate it to the extent that he could overlap the two languages. If subservience to photography yielded a more or less traditional pictorial language, he would approach solutions characteristic of advertising posters and the constant renewal of design favored by digitization. He would never use pre-existing document, for the camera would serve to fix the premeditated acts of his model. Photography would not be of crucial assistance, but merely a step in a process in which no fragment should renounce allegorical allusion that, added to the present, would reveal secrets of intimacy characteristic of women and men. Naturalism and realism would be cleansed of any tendency to return to the past, so as to commit to the path of new expressions achieved by new techniques.

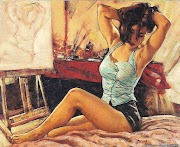

The present series by Victor Rodríguez is the result of a systematic plan obedient to peremptory codes applied to more intimate spheres of the artist's subject (mostly the same women with the fly on her cheek, the artist's companion). They are fully identical with the impulse to undertake simple or baroque intimacy with a variety of approaches and with no concessions to Puritanism. Immediate and even prosaic existence reaffirms a vitality of temporal feelings. Rodríguez manipulates the transitory and his tactic consists in converting vulgarity into subtlety, a decontextualized and therefore provocative subtlety, that questions the scope of dignity. His images are not lacking in psychological research. He delivers no judgements, but imposes a double reading on the viewer: the reality represented and the list of rules intended to constrain it.

Three paintings with explicit references to art, one executed by Victor Rodríguez and the other two by his wife, stimulate particular interest. The acrylic Buen artista/Good artist operates as an aphorism. He, like Van Gogh, cuts off his ear. On his head, a white mushroom, shaped like a brain, contains a peanut. However good an artist one may be or become, one has to have a peasized brain to cut off one's ear after argument over aesthetic questions with an esteemed colleague. Was Van Gogh a "good artist"? Victor Rodríguez seem to ask himself and he answers himself: yes, he was; but it seems absurd that someone capable of concentrating his inventive force on chromatic expressions and in generating color as an intimate experience, would offer his ear on the altar of polemics. That passionate outburst, Victor Rodríguez metaphorically, does not make him any less an artist, as he himself wants to be, though does not set aside the possibility of extreme irritability as a result of his vocation. Mrs. Rodríguez' Libro de Arte/Art Book focuses on a catalogue by Gerhard Richter. Richter is a German artist who stands out for the versatility of his production in the panorama of new artistic behavior from the "New savages to the trans-vanguards". This is true also because he is among those who accentuate pop and the urban scene in their hyper-realistic proposal, even to the point of neo-expressionism. Obliquely, Victor Rodríguez admits to being informed of the various options within the tendency he pursues and that he is prepared to practice by contributing his own voice or experimentally.

In Vándala/Vandal (femenine) Mrs. Rodríguez, her head covered with an Andean cap and her hand in a black wool glove, inconsiderately paints Dali-like moustaches on a poster portrait of a movie star. There is in this an evocative sense of Marcel Duchamp farse. The Latin American vandal displays scandalous Dadaist activity in a hyper-realistic composition, the photographic model for which was taken one winter day in New York. The combination of information is convincing proof that Victor Rodríguez has indeed recycled hyper-realism by making the effort to precisely reproduce a multiplicity of experiential and cultural contents.

0 Comments